How to measure EMF

There are many types of EMF and no single instrument can measure them all. This article explains what frequencies are and presents low-cost instruments which measure different forms of EMF. It is necessary to use various types of instruments to get a more complete picture of the EMF in a particular place.

Keywords: how to measure EMF, gaussmeter, RF meter, how to measure RF, how to measure dirty electricity, which to buy, frequency spectrum

Frequency ranges

EMF radiation is mainly characterized by its frequency and its strength [1]. Some equipment radiates frequencies to communicate, while other equipment radiates unintentionally. Equipment that communicates wirelessly, such as cell phones and FM radio transmitters, uses a variety of frequencies. It is sort of like a symphony orchestra, where some instruments use low-frequency base sounds (like a cello), while others use a higher frequency sound (like a piccolo flute).

|

|

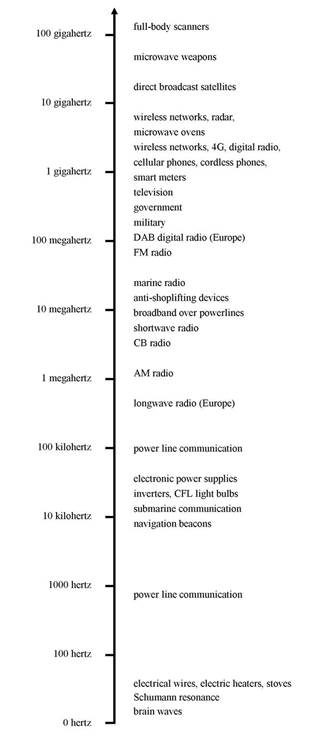

The various frequencies and their sources. This chart is for illustration only; it is not complete, and only shows approximate frequencies. Some sources span a wide range of frequencies, such as radar, which can use frequencies from 325 MHz and up to 80 GHz, depending on the type. Most radars are in the 2 GHz to 9 GHz range. |

The figure gives an overview of the frequency bands, and what they are used for.

The frequency is measured in the unit hertz, which means “cycles per second”. Most people are familiar with hertz from radios—if an FM station advertises that people can find them at “97.9 on the dial,” that means they broadcast on the frequency of 97.9 megahertz (or 97,900,000 hertz.) The EMF transmitted by this station is received by radios and turned into music and speech. However, an FM radio is not good at telling us how strong the signal is, or what goes on across the dial at the same time. To measure the radiation from an FM radio station, as well as from cell phone base stations, Wi-Fi/WLAN networks, etc., we’ll need an RF meter.

An electrical wire in a house also broadcasts a signal, though with a much lower frequency than a radio station. Here it sends out the frequency 60 hertz (50 hertz in some countries), which an FM radio cannot pick up, but a gauss meter can. The wires in a house are much weaker transmitters than those on a tower, but they are also much closer.

If there are a lot of high frequency signals (dirty electricity) on the household wiring, the wires will radiate these frequencies as well. The gaussmeter is largely blind to dirty electricity, so another meter is needed to measure that.

The satellites that beam television and internet services down to Earth transmit on frequencies from 12 GHz and up. (There are no consumer grade instruments that can measure this radiation, but it is much less than terrestrial sources).

If you are trying to measure a radar station, you’ll first need to know more about it, as they can use a very wide range of frequencies. Air traffic radars typically use around 330 MHz, 2.8 GHz or 5 GHz, depending on whether they are for guiding aircraft for landing, air traffic control, etc. Radars used on civilian ships use around 9.2 GHz, while military ships have radars using frequencies from 1.2 GHz up to 18 GHz, with much higher frequencies used by some weapons systems.

All sorts of electronic devices broadcast at different frequencies; most do it on many frequencies at the same time.

For a person who is sensitive to EMF, it is important to know the full picture if trying to minimize exposures to EMF.

The gauss meter

The gauss meter measures the strength of the low-frequency EMF radiation, like that coming from electrical wires (50 or 60 hertz). The better models can also show some higher frequencies (thousands of hertz, kilohertz), which come from some electronic appliances, such as power supplies.

In North America, a gauss meter measures the strength of the radiation in the unit milligauss. In other countries, microtesla is used. (1 microtesla = 10 milligauss).

Two moderately priced gauss meters that are sufficient for most people’s needs: Alpha Labs TriField (left) and Gigahertz Solutions ME 3039B (right).

Cheaper gauss meters are usually only able to show EMF levels down to about one milligauss (0.1 microtesla). That is barely acceptable for healthy people, and inadequate for people sensitive to EMF. People who are sensitive to EMF will need an instrument that can detect at least 0.1 milligauss (10 nanotesla).

We like the Alpha Labs TriField meter, as it does not contain any digital electronics and is thus tolerable to use by even the most sensitive people. We also like the Gigahertz Solutions ME 3030B as it is a little more sensitive than the TriField meter, at a similar price.

The TriField meter can also measure electrical fields and radio waves, but is not sensitive enough to be of any practical use. The ME 3030B meter can measure electrical fields very well.

Whichever instrument you decide to buy, make sure it has three built-in sensors, so it automatically measures in all three dimensions. Some cheaper models have only one sensor and must be turned around to find the highest reading.

For a general survey of an area, simply walk around with the meter in hand and notice what the levels are.

Areas where much time is spent, such as the bed, the favorite chair and the dining and computer areas should be checked more thoroughly. In these places of longer exposure times, it is important to check for EMF where all the body parts will be, both the feet, the head, and in between. The field can be much stronger on the floor than higher up—either because of wires under the floor, or perhaps from electronic equipment placed on the floor.

The human body appears to pick up EMF in all body parts, but some areas, such as the head, may be more sensitive.

Other places to check with a gauss meter are near the circuit breakers and the electrical meter, space heaters, electric stoves and water heater, and various electronic equipment—including those little plug-in transformers. And remember to check on the other side of the wall from an electrical device.

You can also measure a gasoline or diesel car with it. With the engine running, try to measure around the driver’s seat, footwell and dashboard. A regular gauss meter does not measure electric cars and hybrid cars well, because their power system is most powerful at higher frequencies.

More sensitive gauss meters

People with severe electrical sensitivities may need instruments that are more sensitive. Instruments that can detect as low as 0.001 milligauss (0.1 nanotesla) may be needed.

Two very sensitive gauss meters that can detect EMF down to 0.001 milligauss (0.1 nanotesla): Alpha Labs TriField 100XE with external probe (left) and Gigahertz Solutions ME 3951A

We like the Alpha Labs TriField 100XE and the Gigahertz Solutions ME 3951A. The TriField 100XE is all analog, but it is harder to use (see below) than the ME 3951A. The ME 3951A can also measure the electric field with a useful sensitivity.

The 100XE meter is no longer available as new. AlphaLab instead sells the UHS2, which can detect magnetic fields as low as 0.01 milligauss (1 nanotesla).

One of the things these very sensitive instruments can pick up is ground currents, which is electricity which runs in the soil. Some people refer to ground currents as “stray voltage” or “stray currents.” Ground currents typically come from grounding rods that are mounted on electrical power poles, transformers and in buildings. They can reach hundreds of yards away from any human structure.

Large power lines can sometimes be picked up more than a mile away, in very rural areas.

When measuring ground currents, the reading will be the same whether the probe is lying on the ground, or is several feet above it. The EMF level does not rapidly diminish with distance, as it does with a point source.

How to use the TriField 100XE

The TriField 100XE uses an external wand. The wand is an external probe, which does the measuring when plugged in. When not plugged in, the meter works with the standard sensitivity (down to 0.1 milligauss only).

With the probe plugged in, the scale on the meter must be divided by 100 when read. For instance, if the instrument knob is turned to “MAGNETIC (0-3 range)” and the dial shows “1” on the middle scale, it is actually 0.01 milligauss. If it shows “0.6”, that means 0.006 milligauss (which is also 6 microgauss).

If the knob is set at “MAGNETIC (0-100 range)” and the dial points to “4” on the top scale, that means the EMF level is 0.04 milligauss (or 40 microgauss).

To save money and space, the wand measures only in one direction. To get an accurate measurement, it is necessary to perform three measurements at each location.

To measure with the wand, first place the wand horizontally (any direction) and read off the number, once the needle has stabilized. It may be best to remove your hands from the wand, as any slight movement affects the reading. Then turn the wand ninety degrees horizontally in either direction and do another reading.

Finally, stand the wand vertically and do a third reading. The highest reading is the correct measurement for this location [2].

The AM radio

To get an idea of what EMF lurks in the middle range of frequencies, use a simple AM radio. It does not provide a reading on a dial, but instead it allows one to hear EMF emissions from electronic equipment, electrical motors, arcing wires, cables, GFCI outlets and much more, most of which a gauss meter cannot pick up.

A simple, cheap, handheld, analog AM radio is best. Look for one with analog tuning. More sophisticated models with digital controls and digital signal processing can still be very useful, but they may not be as sensitive to electronic static as a simple analog radio.

Simply turn on the radio and set the dial in an area where the least amount of noise is heard, and where there is nothing received from any station. The bottom of the dial range usually works very well. Then walk around and put the radio close to electrical outlets in the wall, exposed wires, fluorescent lights, telephone cords, any electronic equipment, GFCI-protected outlets in the bathroom and kitchen, and so forth.

You can use the AM radio to detect dirty electricity by holding it up against electrical wires that are not near any electronic device. Try to open the breaker panel and hold it against the breakers, but not next to the electrical meter. Be aware that American houses built later than 2008 will have an AFCI breaker, which radiates and creates dirty electricity.

Measuring dirty electricity with an AM radio.

The radio will only pick up static when it is close to the source in most cases. Humans can be more sensitive than the radio and need to keep a greater distance.

Try to move the station dial to the other end of the scale and check around again. Some equipment may sound differently or louder on a different frequency setting.

If the speaker is put against a wall or some equipment, the sound coming from it may be reflected back and sound louder than it is, so you may think there is an EMF problem where there isn’t. It is thus best to hold the radio so the speaker is pointed towards you and away from the item being checked.

Metallic surfaces act like antennas. When the AM radio is held near a metallic surface, it may pick up a far-away radio station. When touching metal, crackles may be heard. This is normal and does not mean there is a problem. The metal doesn’t somehow gather and enhance the EMF that was already there; it merely reflects and channels it.

Radio frequency meter

In the high-frequency bands we encounter a soup of EMF from near and far. In our own homes, there may be cordless phones, cellular devices, a microwave oven, computers and wireless networks. Some of these emissions can also come in from neighboring buildings. Right outside may be wireless smart meters for your gas, water and electricity. From afar, transmission towers of many kinds contribute to the overall level of electro-smog.

Today, there are no areas free from radio frequency radiation. The question is only how much there is.

A great number of instruments are available to warn us about radio frequency EMF, from a simple pocket-device that beeps when the level rises, to an instrument one can point towards a source which will display what frequencies it transmits on.

There are several instruments available below $300 that offer a good compromise between cost, sensitivity and features. They use a variety of units, such as microwatts-per-square-meter (uW/m2), volts-per-meter (V/m), etc. Some instruments have a button to choose the unit.

It is important to get a meter that is as sensitive as you are. Look for sensitivity down to at least 1 uW/m2 (0.00001 uW/cm2). If the advertising for the instrument doesn’t say how sensitive the instrument is, then it is a useless toy.

The RF meter should also cover a good range of frequencies, to pick up the most common sources of RF. Most of today’s emissions are inside the frequency range 500 MHz to 6 GHz (6000 MHz). In the future much higher frequencies will be used for communication. Be aware that many radars already use much higher frequencies. Also, AM radio, shortwave radio, air traffic, maritime radio, etc. may use frequencies below 50 MHz.

For your first RF meter, make sure it has an omnidirectional (3-axis) antenna, i.e. it measures the radio waves from all directions. (Directional antennas look like a fish skeleton; they are used to identity and measure individual RF sources.)

RF meter showing the radiation from a pump at a gas station. The pump has a wireless pay feature that radiates whether used or not.

Using a mobile phone as an instrument is not very useful. The bars show only the signal strength from towers the phone can communicate with. Nearby towers from other carriers are ignored.

There are apps for mobile phones that can give a better idea, but they are still limited to mobile phone towers. They still do not show many other sources, such as smart meters, police, etc.

Consumer grade RF meters use RF sensors that are affected by ambient temperatures. You will likely get a too high reading on a hot day or if the instrument is exposed to direct sunlight.

These instruments are also limited to what is called the “far field” (the “near field” requires special antennas). In praxis that means the instrument will show too low a reading if closer to the RF source than about 4 feet (1.3 meters) [4].

Be aware that consumer grade instruments are seldomly accurate and very often overstate how sensitive they are and how wide a range of frequencies they can detect. Professional EMC laboratories have tested several RF meters and found many of them disappointing. So take whatever results they provide with a lot of salt.

The readings on the display will likely fluctuate a lot. This is normal in an area with many wireless transmitters, as they tend to transmit in short bursts.

Measuring dirty electricity

The AM radio is a crude tool for measuring dirty electricity by holding it up against electrical cables, etc. In some buildings the level of dirty electricity is so strong it crackles an AM radio even if it is in the middle of the room.

If you want more accurate measurements, you will need a special instrument, like the two shown in the picture.

Two meters showing high levels of dirty electricity. They are from Alpha Labs (left) and Stetzer (right).

A sophisticated gauss meter, such as the Gigahertz Solutions ME 3951A, can also measure dirty electricity. Set the range selector to 2-400 kilohertz and Electric field.

The Stetzer meter gives a reading in Graham-Stetzer (GS) units, which is their own proprietary system.

To find sources of dirty electricity, plug the meter into various outlets. The reading will be higher the closer it is to a source.

Dirty electricity can also come from the neighbors. To find out, plug the meter into an outlet on a breaker-circuit that has no electronics on it, and no GFCI or AFCI on it. Turn off the breakers to all other circuits in the house. The meter should then display what amount of dirty electricity is coming from the electrical meter and the neighbors.

Dirty electricity is usually in the range from 10 to 100 kilohertz frequency, but it can go above 1000 kilohertz.

Common sources that generate dirty electricity below 100 kilohertz include most energy-efficient lights (CFL, LED), light dimmers, solar systems with inverters, and all sorts of electronics (computers, televisions, battery chargers, chargers for cordless phones, etc.).

Frequencies above 100 kilohertz are generated by some sophisticated power supplies, and otherwise by electronics that communicate through the wires. These have names such as Broadband over Power Lines (BPL), HomePlug and Power Line Communication (PLC).

Be aware that some instruments for measuring dirty electricity cannot pick up the higher frequencies, as shown in the table below.

|

|

Maximum frequency |

|

AM radio |

1,000 kilohertz |

Things to try

With these tools in hand, it is like being outfitted with a new set of ears. Here is a list of things to try to measure. When measuring, notice how the reading is higher close up, and how it diminishes rapidly with a little distance, and notice how the different instruments react.

· Computer, screen and keyboard

· Wrist watch

· Electronic thermostat and thermometer

· Fluorescent light, low-energy light

· Microwave oven

· Refrigerator, freezer, washing machine

· Electric water heater

· Cordless phone, mobile phone

· Outlets with GFI/GFCI protection

· Electric fence

· Car, car electronics

· Electric power lines

· Night stand clock

· Wireless network equipment

· Battery charger

|

|

|

|

Measuring a

compact-fluorescent light bulb with both an AM radio and a gaussmeter. |

|

Any computer will generate a lot of static in an AM radio.

Checking a rechargeable night light that is controlled by touch. It radiates even when “off.”

Tips on measuring EMF

The levels of EMF may change over time, when measuring ambient EMF. Try to measure on different times of the day, and on both weekdays and weekends.

Some EMF is seasonal. A big power line may give a much higher reading on hot summer afternoons, when everybody runs their air conditioners. Or, the neighbors next door may only generate EMF when they are home and doing certain things.

Radio-frequency radiation can vary dramatically within minutes in areas with many sources, such as cell phones and wireless networks. This can be seen in areas with many shops, apartments, etc.

A common mistake is to walk around with an RF meter and think that certain spots are “hot,” when it is just the ambient level that temporarily peaked. Before considering a spot “hot,” make sure to really verify that with multiple readings, especially if there are no close-by sources.

Some equipment will broadcast on many frequencies. One example is a hairdryer: the heating element will emit EMF on 50 or 60 hertz, while the blower motor will broadcast across many frequencies. Another example is a compact fluorescent (CFL) light bulb.

A computer consists of many parts inside the box and the screen. All parts may generate a multitude of frequencies. There will be a number of transformers (voltage converters) inside, which generate the different voltages needed by various parts in the computer. Each transformer emits EMF in the kilohertz range. The processor chip itself will emit EMF around a few gigahertz (the advertised speed is the frequency of the processor). There are many other components inside the computer case, such as disk controller, network card, etc., which will run (and thus emit EMF) in the megahertz range.

The screen, keyboard, mouse and cables will have their own set of emitted frequencies.

It is actually possible to tune in to a computer, using special equipment. It is then possible to read what is on the screen, right through walls of a building. Intelligence agencies and spies have used this method for decades.

All of these are unintended radiation, that are a byproduct of how a computer functions. Then there is the intentional radiation from Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, etc.

Beware of out-of-range results

All instruments are limited in how high and how low levels they can measure. If your instrument shows a zero reading, it doesn’t mean there is no EMF, it just means the level is lower than it can detect. There is EMF everywhere on earth, in all frequency bands.

The important thing to consider is whether your instrument is good enough, i.e. can it detect EMF low enough to still be important for health. Many low-cost instruments do not.

The Stetzer meter can only measure up to 1999 GS units. If the level of dirty electricity is higher, the instrument will display the number “1”. This is unfortunate, as people may think they get a nice, low reading, when the reading is actually very high. It is not unusual to exceed the range of the Stetzer meter in buildings with solar systems or large machinery (such as big HVAC systems). The dirty electricity meters cannot measure all types of dirty electricity, and will tend to show a too-low value when further away from the source [3].

Beware of accuracy

These are not very precise instruments. Some display a lot of digits, which makes them appear to be more precise than they are. One instrument may show “156.12,” but it may not be more precise than 150 or 160. Sometimes even a wider range.

Not so simple

Remember, it takes a lot of instruments to get a full picture in some situations. A sensitive person may still not feel well in a location where the available instruments show low readings. The instruments mentioned here only provide reasonable coverage of most situations.

Doing good measuring is more complicated than just reading a number off a scale. Sometimes it also requires a basic understanding of the equipment that is measured. There are unfortunately many myths circulating on social media.

You can get a pretty good idea with simple “casual” measurements, as long as you are aware they are just ballpark figures.

Hiring a consultant

You can hire specialists to do these measurements. Unfortunately, in America there are many who offer such services who are quite mediocre. There is no certification program that guarantees competence (except for a Professional Engineer).

When considering hiring a consultant, check for a technical college degree.

Ask to see a sample report, so you know what you will get. A really professional job will likely include the use of a spectrum analyzer and data loggers to show how the radiation varies over time and by sources.

That level of detail costs more and may not be needed if all you want is a general idea.

The author’s arsenal of instruments, which still do not cover all possible situations.

How much EMF is too much?

What levels of EMF are acceptable? That is a good question, with no firm answers. Nobody knows for sure, and it also depends on whether it is continuous exposure—perhaps round the clock—or just for shorter periods of time, like in a car. Some doctors also think that exposures during sleep should be lower than what is acceptable during the day. And then it also depends on whether the person is healthy or electrically hypersensitive.

The official standards in the United States for how much EMF radiation is allowed are based solely on the heating effect on body tissues—the “microwave oven effect.” The other effects are still controversial and totally ignored by the officials. Most other countries have similar standards. All these standards are nearly worthless, but industry interests keep them in place.

Scientists who are independent of corporate and political interests suggest much lower limits than the official limits, though there are not yet any firm numbers. For a list of what various science groups recommend, see the link at the end of this article.

For the middle frequencies—those picked up by an AM radio—the best advice is to avoid places where any static is picked up—especially for the sleeping area.

Researchers keep finding biological effects at lower and lower levels. It may be that there is no level that is fully safe, just as for radioactive radiation. In that case, an “acceptable” level will have to be chosen.

There are no solid standards for acceptable levels of dirty electricity. There is simply too little research available yet. If the AM radio detects dirty electricity, the levels are probably rather high, as such a radio is not very sensitive.

What the instruments do not tell us

This article covers only the types of EMF that appear to be the most important, and which can be easily measured. Types of EMF that are not fully measured by these simple methods include:

• pulsed radio waves

• radar

• AM and shortwave radio

• electrical fields

• ELF/ULF dirty electricity

Digital wireless transmitters, such as digital television and cell phones, use pulsed radio waves. Pulsed radio waves have been found to be more biologically active than the old-style analog radio waves. Our current methods and standards use averaging of these signals, which may be inadequate. Some RF meters have the ability to record the peak of pulsed signals, but there are no standards to compare with, and no guidelines for how long an interval to record those peaks for, among other issues here.

Radar is not a problem in most areas, but near airports, military installations, weather radars and ships, they can be the dominant source of EMF.

AM and shortwave broadcast stations are only located in a few areas, but are often very powerful.

Electrical fields stand between electrical wires and the ground. The field strength depends on the voltage on the wire and the distance between the wire and the ground. The strength is the same whether current runs through the wire or not, the wire only needs to be connected to an electric source (i.e. energized). This field is not the same as the magnetic field, which is measured by a gaussmeter.

Most researchers consider the electrical field much less important than the magnetic field. However, some people do seem to be sensitive to it, especially when there is also dirty electricity present.

ELF/ULF stands for Extremely Low Frequency and Ultra Low Frequency. Some PLC smart meters communicate by these frequencies, which are intolerable to some sensitive people.

To adequately measure all these types of EMF would require several additional instruments, some of which are expensive or complicated to use. Most people would not need these additional measurements.

There can also be natural phenomena, which are poorly understood and not measurable by any of today’s instruments. Called geopathic stress, they can be as bothersome to sensitive people as man-made EMF. The author of this article was very skeptical of geopathic stress until encountering such a case, where no other explanation was possible.

When a person who is hypersensitive cannot live in a place that shows up fine on our instruments, it may simply mean that our instruments and present knowledge are inadequate to the task. We do not understand everything, and we do not have instruments that can measure it all.

For more information

What independent scientists suggest as safe EMF limits: www.eiwellspring.org/ehs/EMRguidelines.htm.

For more articles about how to measure EMF in particular situations, go to www.eiwellspring.org/measureemfmenu.html.

For articles on how to remedy EMF problems, go to: www.eiwellspring.org/shielding.html.

2007 (updated 2024)

________________

[1] Other characteristics include the shape of the signal (sinus wave,

square wave, irregular, etc.), whether it is continuous or pulsed, and many

other factors.

[2] The more precise number is the geometric sum of the three readings, but such accuracy is not needed, and the instrument is not that accurate anyway. If the three readings were 2, 3, and 10, the more correct number is the square root of (2 x 2) + (3 x 3) + (10 x 10) = 10.6.

[3] They only measure differential mode dirty electricity, not common mode. Longer wires convert the noise on the line to common mode.

[4] The far field begins about four wavelengths from the RF source. At 900 MHz the wavelength is about one foot (33 centimeters). At 6 GHz the wavelength is 2 inches (5 centimeters).